John the Fearless

John the Fearless

Son of Duke Philip the Bold and Margaret III of Flanders, John was born in the Ducal Palace at Dijon on 28th May 1371. A diplomatic union was arranged for him to Margaret of Bavaria, with the marriage taking place in 1385.

As heir to the Duchy of Burgundy, John led forces in France’s army as they supported the Hungarians against the Turks. It was in this war, at the Battle of Nicosea, that John acquired the moniker ‘the Fearless’. The campaign also demonstrated John’s weaknesses, his rash decisions leading to his own capture and a disastrous campaign by the European allies.

Inheritance of the Duchy of Burgundy

Upon his father’s death in 1404, John inherited the Duchy of Burgundy and his father’s political role within France. His father had been the fourth youngest son of King John II and a senior courtier. The following year he inherited the lands held by his mother, giving him a large amount of influence and control in the Low Countries.

At the time, France was politically in turmoil. The bouts of ill health suffered by King Charles VI had made Government unstable. With the King frequently unable to fulfil his duties, the most senior nobles squabbled and fought to take control.

Clash with the Duke of Orleans

The conflict was mainly between John the Fearless and the Duke of Orleans. The two factions used underhand methods to seize control. For example, the Dauphin was kidnapped more than once, and John manipulated an ill Charles VI into making him the princes guardian. The in-fighting had to stop, for the good of France, and the Duke of Berry attempted to reconcile the feuding Dukes. It was peace in appearances only, and one that was not to last long. In November 1407, the Duke of Orleans was assassinated on the orders of John the Fearless.

Source Material: The Assassination of the Duke of Orleans

The man Thomas approached the duke and falsely declared: ‘My lord, the king bids you to come to him without delay, because he has something concerning himself and you which he must discuss at once.’ When the duke heard this alleged order from the king he immediately leaped on his mule to answer the summons. In his company there were two squires on one horse and four or five foot servants in front and behind carrying torches: his other followers were in no hurry and he was poorly attended that day, though he maintained in Paris a staff of quite six hundred knights and squires. At the Porte Barbette the eighteen men were waiting for him in the shadow of a house with their weapons concealed from view. The night was dark. As the duke approached the gate they leapt upon him in a wild fury, and one shouted: ‘Kill him!’ dealing him a blow with his axe which severed his hand clean at the wrist.

The duke, seeing such a cruel attack made upon him, shouted out loud, ‘I am the Duc d’Orléans’, to which some of those who were striking at him answered: ‘That’s just what we wanted to know.’ At this the rest of the men joined in, and shortly the duke was knocked off his mule and his head smashed with blows that the brains ran out on the roadway. Even then they turned him over and over, so hacking at him that he was very soon completely dead. With him was also killed a squire who had been his page; when he saw his master on the ground he lay upon him to protect him, but to no avail.

Enguerrand De Monstrelet, Chronicles

It was a crime to which John the Fearless admitted and argued was justified.

At that time in the kingdom of France the duke of Orléans, just while his lusts were taking a holiday from acts of adultery and from prostitutes and paramours, was slain by a certain knights, whose wife he had been accustomed to ravish. And because the duke of Burgundy dared to defend the action of this knight, he was proscribed and loaded with many other penalties, and so left France for the time being. Afterwards he was captured and put in prison, but he was released on condition of his taking Calais. Actually the duke had been justified by a learned clerk, Master John le Petit, who in the royal house of St Paul in Paris had put forward eight points to prove that the same duke of Burgundy had lawfully and deservedly had the duke of Orléans put to death.

Thomas Walsingham, Chronica Majora

Burgundy, the Cabochienne Revolt and the feud with the Armagnac Faction

Murdering his foe did not end the dispute. The new Duke of Orleans was not of age but his uncle, the Count of Armagnac, led his families cause: leading to the faction being known as the Armagnacs. An uneasy truce between the sides was arranged from 1410 onwards, with periods of John being in Paris, where he was rumoured to be a lover of the Queen, or in Burgundy. He was present as the Cabochienne Revolt erupted and fuelled the situation by coercing the King into signing the Ordonnance and supporting the Cabochienne rebels.

Those events of 1413 led to John returning to Burgundy. Soon after, England under Henry V began to exercise pressure on France. This situation meant that the French needed to reconcile their differences with John, in order to sure up the army that would most probably (and was) be needed to face the English. It also presented Henry V with the tantalising prospect of being able to woo John into an alliance against the French crown.

Burgundy, Henry V, and post-Agincourt developments

John courted both sides as diplomacy between France and England continued. Eventually, he was pushed into deciding. Henry V made it clear that he expected John to acknowledge his right to be King of France. John would not give it. Nor did he personally join the army of France that faced the English invasion, thus avoiding the disaster that befell the nobility at Agincourt.

Following Agincourt, John once again was prominent in the French court. In 1418 he installed himself in Paris and styled himself as being the Kings protector. In reality he had all but seized power and was in open conflict with the Dauphin. John was incredibly paranoid in this period. His Paris residence was a one bedroomed tower that was easy to defend.

Assassination of John the Fearless

The paranoia was not without good cause. In 1419 John and the Dauphin made terms at Pouilly. The Dauphin then asked for a further meeting, on a bridge at Montreau. John the Fearless was assassinated on the bridge, mirroring the manner in which his own men had dispatched the Duke of Orleans.

Under the leadership of John the Fearless, Burgundy had grown in strength and significance. Even when absence, he had been a figure of note in and around the French court. At times controlling policy, at others rousing revolts and seemingly always at the centre of political intrigues.

His assassination was a turning point in French politics. Philip the Good, John’s successor, turned his back on his father’s assassins and forged an alliance with England. It was an alliance that enabled the English to continue posing a threat to France for decades to come: it was still a military threat in 1475.

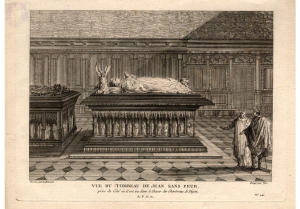

by François Denis Née, after Jean Baptiste Lallemand. Line engraving, 1780s or 1790s

NPG D8058. © National Portrait Gallery, London – Creative Commons Licence