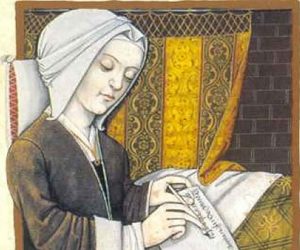

Christine de Pisan

Christine de Pizan was born in Venice, Italy, in 1364. Her father was appointed astrologer to the French court in 1368 and from this point onwards, Christine’s childhood was spent in Paris. Aged 15 Christine married Estienne de Castel, who became a secretary to the court. Following the deaths of her father and husband, Christine turned to writing in order to support herself, her mother and her three children. In doing so, Christine became the earliest professional female writer in France, and her works have remained significant ever since.

Christine had benefitted from her upbringing in and around the French court. Educated, she had acquired skills manufacturing manuscripts and had acquired writing skills suited to several audiences. It meant that when she was widowed, aged 25, she had a trade to fall back on.

The need for an income was more complex due to lawsuits that were lodged regarding the salary due to her now deceased husband. It saw litigation against Christine from the Archbishop of Sens and François Chanteprime, both of whom were counsellors to the King. It was a period that she reflected on in her writing, noting that to survive, she had been obliged to ‘become a man’ in terms of her approach to work. In The Book of the Three Virtues she explains that widows must “be constant, strong, and wise… not crouching like a foolish woman in tears and sobs without any defense, like a poor dog who cowers in a corner when all others attack him”.

For the first ten years after the death of Estienne it is unknown what Christine did to support her family. Clues in her writing hint at her having an income from official sources, perhaps through administrative writing through her contacts at court.

From 1399 onwards, Christine’s life and work is well documented. She published a ten volume collection of her works in this year, and presented ‘The Duke’s Manuscript’ to Duke Jean of Berry. The duke of Berry was just one of a number of high profile patrons that she acquired. Philip the Bold of Burgundy commissioned a history of King Charles V, Queen Isabella of Bavaria also acted as a patron, and her works also gained the attention of the English nobility, with the 4th Earl of Salisbury also being one of Christine de Pizan’s patrons.

A female writer was quite unusual at this time. There are other examples of women of the fourteenth century who wrote, but most were linked to religion, rather than commentating on wider society. Christine herself was aware of the value of being an exception to a rule, noting her success was largely because “poetry written by a woman was such a novelty”.

Her best known work is The Treasure of the City of Ladies. It was a manual of instruction and education, dedicated to Princess Margaret of Burgundy.

Extracts from The Treasure of the City of Ladies

One day I was surrounded by books of all kinds… my mind dwelt at length on the opinions of various authors whom I had studied… it made me wonder how it happened that so many different men – and learned men among them – have been and are so inclined to express… so many wicked insults about women and their behaviour… it seems that they all speak from one and the same mouth… Thinking deeply about these matters, I began to examine my character and conduct as a woman and, similarly, I considered other women whose company I frequently kept, princesses, great ladies, women of the middle and lower classes, who had told me of their most private and intimate thoughts… No matter how long I studied the problem, I could not see or realise how their (male writers) claims could be true when compared to the natural behaviour and character of women…

I know a woman today, named Anastasia who is so learned and skilled in painting manuscript borders and miniature backgrounds that one cannot find an artisan in all the city of Paris… who can surpass her… People cannot stop talking about her. And I know this from experience, for she has executed several things for me which stand out among the paintings of the great masters…

I am amazed by the opinion of some men who claim that they do not want their daughters or wives to be educated because they would be ruined as a result… Not all men (and especially the wisest) share the opinion that it is bad for women to be educated. But it is very true that many foolish men have claimed this because it upset them that women knew more than they did…

The City of Ladies as it is most commonly known sees the author approached by three allegorical ladies: Reason, Rectitude and Justice, who charge her with the task of creating a City of Ladies. Here, she clears away debris left by anti-feminist writers and her detractors.

At the same time as Pizan was writing City of Ladies, she was also working on The Book of Body Politic [1404-1407], a tract that delivers lessons on the virtues to be held by a prince. This is political philosophy, also touched upon in Letter from Othea, which deals with different segments of society. Christine’s description mirrors a traditional view of feudalism in some ways, by constructing a body with the prince as the head, knights as the limbs, and the lower classes as the feet.

Christine’s writing often revolved around the theme of love. Her earliest writing reflected on her grief at losing her husband, and later in her writing career she returned to love poetry, publishing Cent Ballads d’Amant et de Dame (One Hundred Ballads of a Lover and a Lady) in 1410.

The internal conflict that beset France following the assassination of the Duke of Orleans affected Christine de Pizan’s writing. In the Book of Peace, 1412, she reflected on the troubles. The defeat of the French army and death of many of her patrons, and thousands of soldiers, at the Battle of Agincourt saw Christine write a letter of consolation to the bereaved, “L’Epistre de la Prison de Vie Humanie” (A Letter concerning the Prison of Human Life). Following this, Christine retired to a convent.

Christine broke from her retirement to write one last time, on the subject of Joan of Arc. Le Ditié de Jehanne d’Arc is the only French language publication that was published about Joan of Arc during her lifetime, it being published in 1429.

Extract from Le Ditié de Jehanne d’Arc

She (Joan of Arc) drives her enemies out of France, recapturing castles and towns. Never did anyone see greater strength, even in hundreds of thousands of men… What honour for the female sex… the whole Kingdom – now recovered and made safe by a woman… And so, you English, draw in your horns… A short time ago, when you looked so fierce, you had no idea that this would be so… You thought you had already conquered France and that she must remain yours. Things have turned out otherwise, you treacherous lot! Go and beat your drums elsewhere, unless you want to taste death, like your companions.

The work of Christine de Pizan had a long lasting and profound impact on Western Europe. Her works were used as an educational tool for Queens, Princesses and other noble ladies. They were also utilised as training manuals for men, perhaps most unusually seeing her work, Faytes of Arms, printed at King Henry VII’s request by William Caxton in England in 1489.

Links

The Making of the Queen’s Manuscript, British Library

King’s College. Bibliography and Annotated Bibliography.